Vere

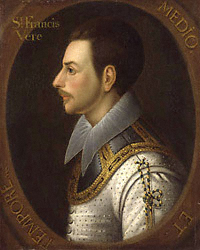

[de Vere], Sir Francis (1560/61–1609),

Fighting Vere. Francis was an army officer and diplomat,

was the second son of Geoffrey Vere (c.1525–1572?) and his

wife, Elizabeth (d. 1615), daughter of Richard Harkyns (or Hardekyn)

of Colchester, Essex. He was born in 1560 or early in 1561, at either

Crepping Hall or Crustwick: both properties in Essex, owned by his father,

who was the fourth son of

John de Vere, fifteenth earl of Oxford [see under

Vere, John de, sixteenth earl of Oxford]. Thus Francis was close kin of

the holders of the premier earldom in England—something he never forgot and

which he used to his advantage.

Vere

[de Vere], Sir Francis (1560/61–1609),

Fighting Vere. Francis was an army officer and diplomat,

was the second son of Geoffrey Vere (c.1525–1572?) and his

wife, Elizabeth (d. 1615), daughter of Richard Harkyns (or Hardekyn)

of Colchester, Essex. He was born in 1560 or early in 1561, at either

Crepping Hall or Crustwick: both properties in Essex, owned by his father,

who was the fourth son of

John de Vere, fifteenth earl of Oxford [see under

Vere, John de, sixteenth earl of Oxford]. Thus Francis was close kin of

the holders of the premier earldom in England—something he never forgot and

which he used to his advantage.Formative years

Little is known of Vere's early life. His connection to the de Vere earls of Oxford was of use to him early, for John de Vere, the sixteenth earl, left a legacy of £20 to him while he was still an infant. As befitted descendants of one of the foremost generals in the Wars of the Roses, Francis, his elder brother, John, and both his younger brothers, Robert and Horace Vere, all received training in the art of war from a young gentlemen of puritan persuasion with some military experience, William Browne, who seems to have been a retainer of the family—perhaps of the senior branch rather than of Geoffrey Vere, who was not wealthy. Thus from an early stage the brothers were intended for, or at least had an interest in, military careers and, in the event, all served as soldiers (Browne, who was later knighted, served alongside the Veres in the Netherlands.)In his late teens Francis Vere travelled through Europe, as did many young English gentlemen in this era. The English ambassador in Paris reported that ‘two young Veres’, clients of the earl of Oxford, were in France in July and September 1577, hoping to fight in the country's sixth war of religion since 1562, but with the royal (Catholic) army (CSP for., 12.14, 192). The two were probably John and Francis (the latter then about seventeen) who were of course connected to Oxford. Moreover the chief royal general was the duke of Guise and in later life Francis recalled that he was in Paris ‘when I was very young’ where ‘I was for a time with the Duke of Guise … [but] was called thence by her Majesty's command and made to know the error of that course’ (Salisbury MSS, 17.494). Presumably the two young Veres were simply seeking actual military experience, but in later life none of the brothers would have contemplated serving a Catholic prince against protestants: indeed Horace was strongly Calvinist. Not much later Francis travelled to eastern Europe. In a letter of 1589 Sir Francis Aleyn described Vere (whom he called ‘my brother’) to his friend Anthony Bacon as ‘he that made the voyage with me into Polonia’ (LPL, MS 657, fol. 247), a trip attributed by Vere's early twentieth-century biographer Markham to ‘about 1580’ (Markham, 26).

Vere's biographers all agree that he had little or no military experience and none in the Netherlands before joining the royal army sent by Elizabeth to aid the Dutch republic in 1585. In fact he served in the Netherlands in 1581 and 1582. The Dutch at this time had some 3000 English soldiers in their employ—mercenaries, but also motivated by confessional zeal to aid their fellow protestants against the Spanish. Vere was a gentleman volunteer in the company of horse led by the famous Welsh professional soldier Roger Williams, whose lieutenant was John Vere: Williams later boasted that Francis's first service was ‘under his charge’, and both brothers are listed in Williams's muster roll of August 1582 (TNA: PRO, SP 78/24, fol. 132r; CSP for., May–December 1582, 260). Francis Vere helped to suppress a potential mutiny against the general of the English in Dutch employ, John Norris. Vere and other gentlemen rankers rallied to their general with ‘dagger drawn’ and cowed the soldiers, who had gone unpaid for some time (CSP for., May–December 1582, 258; Stowe, 805).

Thus Vere had a good deal of military experience, including an education in what contemporaries called the ‘most fit school and nursery to nourish soldiers’ of the time (Motley, 1382)—the Dutch revolt against Spain. The English army in the Netherlands, moulded by Vere in the 1590s, would in turn come to be regarded itself as a finishing school for soldiers.

Apprenticeship: the Netherlands, 1585–1589

In December 1585 Francis Vere, still only twenty-five, joined the English army of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, in the Netherlands. Late in February 1586 he joined the company of lancers commanded by his cousin, Peregrine Bertie, Baron Willoughby d'Eresby (which was in the states general's pay, so Vere was still in a sense a mercenary). Willoughby's troopers, including Vere, distinguished themselves in several actions against the Spanish in summer and autumn 1586 and in November of that year Vere received his first independent command, as captain of a company of foot in the royal army—the first time he was in the pay of his own nation.Vere's company was originally in the garrison of Bergen-op-Zoom, commanded by Willoughby, but in summer 1587 was moved to Sluys, which from 8 June to 4 August 1587 was besieged by the duke of Parma, Spain's commander-in-chief and a ‘new Alexander’ according to contemporaries. Sluys eventually fell, despite great efforts to relieve it by Leicester, but under Vere's old commander, Williams, the garrison fought heroically before it was obliged to accept terms. Vere, twice wounded, made his reputation among both friend and foe by his gallantry. As Williams later recalled, Vere (‘marked for the red mandilion’ that he habitually wore) ‘stood alwaies in the head of the armed men at the assaults’; and, being ‘requested to retire’ because of his wounds, ‘answered, he had rather be kild ten times at a breach, than once in a house’ (The Works of Sir Roger Williams, ed. J. X. Evans, 1972, 48).

Leicester's failure to relieve Sluys, combined with various misjudgements in his administration, led to his resignation and replacement in December 1587 by Willoughby. Vere was back in Bergen, which by autumn 1588 was Parma's new target. The Spanish hoped to wipe out the stain of the Armada's defeat. Instead the city's (mostly English) garrison inflicted on the new Alexander his first defeat. Vere was wounded again and distinguished himself in command of the partly detached forts that commanded Bergen's access to the sea; he was one of three officers singled out in Willoughby's dispatches to Elizabeth for bravery, and was knighted.

Vere was now given leave and returned home with a letter of introduction from Willoughby to Lord Burghley, Elizabeth's chief minister. Vere was already acquainted with Sir Francis Walsingham and Robert Devereux, earl of Essex, prominent counsellor and courtier, respectively. In short order he won the esteem of Burghley who in turn introduced him to Elizabeth; her impression of the young paladin was evidently also favourable. In February 1589, after spending the winter at his family home, Francis returned to the Netherlands, accompanied by his brother Robert.

The trip to England made Vere personally known to the greatest figures in the realm, allowing Willoughby, on Vere's return, to appoint him sergeant-major-general—effectively second in command of all English forces in the Netherlands. (Confusingly Vere was paid from 3 December 1588, but it seems clear he was not appointed until after his return to the Netherlands.) This was a remarkable achievement for a man still not quite thirty who had yet to exercise an independent command in the field, and who for all his connections was a mere younger son of a country gentleman. There was no doubt that Vere was valiant and honourable, the two most important qualities for a sixteenth-century general; and during the siege of Bergen he showed he was, in addition, ‘a prudent adviser … a cautious commander and a resourceful contriver of stratagems’ (Markham, 132–3). Even so, the appointment was still something of a gamble.

Vere's rapid rise owed much to Willoughby's patronage, but there were also strategic and political dimensions to his appointment. Willoughby had already asked to be relieved of command in the Netherlands for personal reasons and his sergeant-major-general would most likely replace him. He and Leicester had directed the Anglo-Dutch armies, but from 1589 England prosecuted the war against Spain by sending armies to France and even the Iberian peninsula. The numbers of English troops in the Netherlands dropped and did not reach the heights of the late 1580s again until the dawn of the seventeenth century. Those troops' commander-in-chief would thus be subordinate to the Dutch, rather than setting the operational agenda, and so did not have to be a peer. Furthermore Leicester and Willoughby had each exercised considerable political power, but often neither wisely nor well—Leicester, in particular, had affronted the queen by his vice-regal pretensions. The English army in the United Provinces was a potential power-base. Elizabeth and her ministers wanted as its commander a man who could not abuse his position. As long as he had the necessary basic military credentials, then modest domestic wealth and status might make him an attractive candidate for high military office, rather than otherwise.

In spring 1589 Willoughby duly retired to England; from May, Vere was formally in command of all English troops in the Netherlands, except those in the garrisons of the cautionary towns of Flushing and Brill (Dutch, but in English hands for the duration of hostilities) which remained under their respective governors. However, Vere kept the rank of sergeant-major-general: he was not appointed to the office of lieutenant-general, held by Leicester and Willoughby. If this reflected the fact that he was a commoner, not a peer, it also reflected the wish of the crown to keep control of its general across the narrow seas. Vere never forgot this, but would still be able to use his primacy in military affairs to achieve a social eminence that transcended his relatively modest origins.

Elizabeth's general, the states' auxiliary, 1589–1593

From August 1589 Vere was in sole charge of the English army of assistance in the Dutch republic. His appointment was a surprise to the Dutch—understandably so. However, Vere soon showed that he could exercise tact and discretion in dealing with England's allies, while he endeared himself to them by his energy and daring. He led from the front, but showed great ability from the very start of his command.In October 1589 Vere led 900 English foot to join a small Dutch army in Gelderland (in the eastern Netherlands) under the province's stadholder, Count Adolf von Nieuwenaar. When the count was killed shortly after Vere's arrival the states of Gelderland, remarkably, asked Vere to take command. He won a victory in the field over a small Spanish army (in which his horse was killed and he was again wounded) before returning to the main part of the republic and going into winter quarters around Utrecht. He had attracted the attention of Maurice of Nassau, stadholder of the Netherlands and Zealand and captain-general of the United Provinces. In March 1590 Vere led a 600-strong English contingent (including his recently arrived brother Horace as well as Robert Vere) in the army under Maurice that stormed Breda. That summer Vere operated with a detached force in initial moves against Nijmegen and then in October he accompanied Maurice on a raid on Dunkirk in which Vere was again wounded.

Also wounded with him was Count van Solms, who had participated in the defence of Bergen. Both men were in Maurice's trusted inner circle of commanders, along with another veteran of Bergen, Marcelis Bacx; Count van Hohenlohe (who had been captain-general in the 1580s); Floris van Brederode; Daniel de Hertaing, seigneur de Marquette; and Maurice's cousin, William Louis of Nassau, stadholder of Friesland. If not quite the diadochi of Alexander the Great, they were still a remarkably talented group of soldiers. Each year in the 1590s Maurice went on campaign, each year reducing another great Spanish stronghold; each year it was these men who were chosen to accompany the prince. That Vere was one of this élite says much about him and about the trust placed in him at this time by Maurice and the states general. As a Dutch chronicler wrote, Vere was ‘a stout and gallant man, greatly favoured by the States above any other foreigner’ (‘een cloeck dapper man, den Landen boven alle andere vreemde seer aenghenaem’; Orlers, 79).

1591 saw sweeping success for Maurice and the Dutch army. In May Vere's men put into practice a clever ruse (probably planned by Maurice, though Vere later claimed the credit) by which the city of Zutphen was taken without a siege. The army then moved on to Deventer, which four years earlier had been betrayed to Parma by an English Catholic governor. Maurice now retook it very swiftly, largely owing to the courage of his English troops (though Vere, again, later took to himself and his troops more credit than they were probably due). Maurice then moved on against the important city of Nijmegen. Investing such a fortress was a complex operation; siege lines covered many miles. Vere was given a detached command and handled it well; so effectively was Nijmegen blockaded that in the end no assault was necessary. Sir Francis was one of five officers singled out by the Dutch for praise at the end of 1591's operations.

The summers of the next two years witnessed less frenetic campaigning, but diplomacy was inevitably a major part of Vere's duties as commander of an expeditionary force in a foreign country. There was much scope for disagreement between the United Provinces and England over the English troops' conditions of service. Equally Elizabeth used the Netherlands as a strategic reserve of experienced troops to serve elsewhere. Sir John Norris, for example, commanded an English army in Brittany from 1591 to 1594, while Essex led an expedition to Normandy in 1592: both drew on English troops from the Netherlands. In addition Elizabeth had her own preferences for strategy in the Netherlands, but her priorities were not always those of the states general. The burden of arranging for the transfers of men and of requesting naval support from the states, and of cajoling the Dutch into the action recommended by Elizabeth, fell mostly on Sir Thomas Bodley, the English ambassador, but the English commander-in-chief was necessarily a party to such negotiations. Vere handled himself well and learned from Bodley's successes (and mistakes).

Meanwhile Vere was wounded when leading the English troops in the storm of Steenwijk in 1592, and ably seconded Maurice at the siege of St Geertruidenberg in 1593. It fell before the end of the summer and Vere was able to go home, where in the parliamentary elections of 1593 he was returned as MP for Leominster. He owed his election to the earl of Essex, who as part of a plan to monopolize the patronage of English military officers, ‘cultivated Sir Francis Vere’ (Hammer, 218). This was welcomed by Vere, who increasingly looked to the earl for patronage.

Vere did nothing of note in this parliament and it was his only real attempt to enter the English domestic political arena. He did not lack political skills, as his increasing involvement in diplomatic negotiations with the Dutch revealed. However, he lacked a power-base in England and generally was content to concentrate on military affairs; then, too, he was a significant player in Dutch affairs. How far he was valued by his allies was made clear during this visit home in late summer 1593, when the states general offered him a pension, on top of his salary from the English government. Unusually, Elizabeth permitted Vere to accept it, and in replying to the states general declared she, like they, knew Vere ‘for a gentleman very well accomplished in all the virtues and perfections, as much civil as military’ (‘nous le cognoissons pour gentilhome si bien accomply en toutes vertus et perfections, tant civiles, qu'appertenantes a la guerre’; Nationaal Archief, liassen Engeland 5882–II, no. 291).

It is unsurprising, therefore, that the states now turned to Vere in an attempt to get more English troops. Maurice was planning in 1594 to reduce the great Spanish fortress of Groningen, key to the eastern Netherlands, which would inevitably be a lengthy and complex campaign, requiring a large army. Maurice wanted Elizabeth to enhance the English field army in the Netherlands, but the already considerable financial burden of England's multi-front war with Spain made Elizabeth reluctant to raise more troops. In autumn 1593, therefore, the states general contracted with Vere to raise a new, separate, English regiment of ten companies, at the states general's expense and to be paid by them, but commanded by Vere, who was empowered to choose all the officers. The desire to increase his authority and no doubt the desire to strike strong blows against the enemy led Vere to accept this commission, which was parallel to his queen's commission. He was once again, in some senses, a mercenary.

Serving two masters, 1594–1599

By March 1594 the companies of Vere's mercenary regiment were arriving in the Netherlands; they were quickly deployed to the campaign against Groningen. The siege, in which Vere was wounded again, lasted well into the summer, but on 15 July Maurice and William Louis, who commanded in the east for the states general, made a triumphal entry into the city. That autumn Vere operated in the north-east of France, whose king, Henri IV, was also at war with Spain: Vere led a Dutch contingent to aid the French. In the following year, 1595, Maurice contented himself with more modest operations, but had the worse of manoeuvrings against the Spanish, in the course of which the rival armies' cavalry clashed. In this action Robert Vere was killed. Evidence differs as to the circumstances, but one account indicates that he was murdered after being taken prisoner. This is not unlikely, for only a few weeks later Vere took a small Spanish fort and had half the defenders killed in cold blood. It was in some ways uncharacteristic and perhaps best explained as an act of revenge, but it does reveal the ruthlessness of which Vere was quite capable.Now, however, Vere was recalled to national service. Essex had been given permission to lead an assault on Spain itself—a grand strategy of which Vere approved and which he may have helped Essex to formulate. Bodley had retired and it was Vere who obtained the support of the states general for the expedition, which he then joined with a thousand veterans. Essex was lord general and Vere lord marshal and lieutenant-general of the army accompanying the fleet, of which the rear-admiral was Sir Walter Ralegh. Ralegh was more important at court and claimed precedence over Vere, but Sir Francis would have none of it: ‘there passed some wourdes’ between the two, so hot that some feared it would ruin the venture (LPL, MS 657, fol. 5v). Essex eventually patched up the quarrel and, in the eventual storm and sack of Cadiz, Vere won considerable distinction—plus nearly £4000 worth of booty.

By January 1597 Vere was back in the Netherlands: his later claim that he spent the winter at court must be due to a lapse of memory or to the inchoate state of his memoirs. On 24 January 1597 Vere was instrumental in the complete rout of the Spanish army in the battle of Turnhout, in which his horse was killed under him again. Both at the time and in his Commentaries Vere took most of the credit, resulting in a bitter dispute with Sir Robert Sidney, governor of Flushing, who also fought well. In fact the credit was probably due equally to Hohenlohe, Solms, Vere, and Bacx, who all showed great initiative and tactical skill and ‘were greatly honoured’ by the Dutch (Orlers, 117). It was the first battlefield victory over Spanish troops for nearly twenty years.

That summer Essex led an expedition to the Azores: Vere accompanied him, again as lord marshal. This venture ended in disappointment, largely because of Essex's mistakes—these included his treatment of Vere. The earl appointed his friend Lord Mountjoy as lieutenant-general, an office Sir Francis had expected, since he had executed it so capably at Cadiz. Vere could do little but accept his patron's decision, but injured pride and frustration at the mishandling of the expedition led him to turn decisively against Essex. On his return he also metaphorically crossed swords again with Sidney and Ralegh over military issues. Vere's increasing unwillingness to defer to anyone reflected his confidence in his own abilities and experience.

It also no doubt reflected Vere's own increasing security. The longer he held his position in the Netherlands, the more indispensable he became. Both English and Dutch governments had become accustomed to working with Sir Francis. This was manifested when in 1598 England and the United Provinces renegotiated the arrangements by which the war against Spain was prosecuted. A new treaty, most satisfactory to Elizabeth, was signed in London on 16 August 1598—but it resulted from hard bargaining conducted by the new English ambassador in the Hague, George Gilpin, and by Sir Francis Vere, who was accredited as special envoy to the states general and had conducted negotiations throughout June. Vere's reward came in the autumn, when he was made governor of the cautionary town of Brill—filling the vacancy left by the death of Lord Burgh, despite the hopes of lords Cromwell and Grey de Wilton, who lobbied hard for the post, and the opposition of Essex. Vere's good opinion of himself was shared by the queen and her new chief minister, Sir Robert Cecil.

The major provision of the treaty in 1598 was that all English field companies be put into the pay and under the command of the states general from January 1599. The cautionary garrisons were excluded and Elizabeth reserved ultimate authority over the rest, but almost all the English troops in the Netherlands were once again under Dutch control. As soon as the treaty went into effect in January 1599 Vere's sergeant-major-general's commission from Elizabeth was matched by one from the states general, making him ‘generael over alle de compaignien Engelschen’ and giving him the full burden (‘last’) and power (‘macht’) ‘over die Engelsche Capiteynen, Officieren & soldaten’ in Dutch pay (Nationaal Archief, archief van de staten-generaal, no. 12270, fol. 169; Nationaal Archief, Oldenbarnevelt archief, no. 2977). Vere was the only foreign general in the states' army and commanded all English troops in the Netherlands, save in Flushing, with a power that was almost absolute. However, his main paymaster was henceforth the Dutch republic, which was increasingly seeking to integrate all its foreign troops into a centralized military structure. Sir Francis Vere—basking in his new status—may not have foreseen it, but trouble lay ahead.

Apogee, 1599–1603

For the moment, however, Vere was still irreplaceable. He was the only man able to fulfil two functions: first he could command the English troops in the field effectively while being trusted by both sides to do justice to their own military priorities; second he was able both to convince the states to redeploy those troops to suit Elizabeth's strategic priorities and to persuade her to give additional assistance when the Dutch needed it. Vere was even a popular figure at home. In October 1599 a stage version of the battle of Turnhout attracted good audiences: the actor playing Vere was identifiable by his (false) beard and distinctive clothing, as one eyewitness affirmed—clearly Vere was now a public personality.It was in these years indeed that Vere won his greatest fame. In summer 1600 he commanded one of the three divisions of the army with which Maurice made a daring amphibious invasion of Flanders. Outmanoeuvred by the Spanish under Archduke Albert of Austria, the Dutch army was brought to battle near Nieuwpoort on 2 July 1600. The result was the most celebrated battle of the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands and a great victory for Maurice. It has been analysed many times and it seems clear that, again, Vere claimed more credit than he was due in his Commentaries. Maurice, in particular, is made to appear indecisive, and readers could easily conclude that Vere was chiefly responsible for the victory. Indeed while his dispatches at the time were taken by some Englishmen to show ‘that the Ennemy was overthrowen by the Valor of the English, and the good Direction of Sir Francis Vere’, others commented on the self-congratulatory note of Vere's ‘letters to the counsaile’. The well-informed John Chamberlain wrote sardonically that these gave a ‘relation … so partiall, as yf no man had strooke stroke but the English, and among the English no man almost but Sir Francis Vere.’ Yet even Chamberlain did not doubt that Vere had played a great part. Indeed Elizabeth received letters from the Dutch government ‘in commendation of our nation, but especially of his great service that day’, and ‘attributing the Victory to his good Order and Direction’; she herself declared Vere to be the worthiest captain of her time (Sydney and others, 2.204; Letters of John Chamberlain, 1.102). In fact Vere commanded the advance guard which made a skilful fighting withdrawal, and then, together with Maurice, led the counter-attack that swept the Spanish from the field in disarray. He was wounded in three places and again had his horse shot underneath him. He did not win the battle himself, but what he did was most praiseworthy.

Vere's heroic defence of Ostend followed in 1601. The siege of Ostend (one of the greatest of the century) from July 1601 to September 1604 is referred to in Hamlet and in the Atheists Tragedie of the Jacobean dramatist Cyril Tourneur, who himself served there. But for Vere's determined initial resistance the city would have fallen much earlier. The Dutch had advance warning of Spanish plans and deliberately shipped Vere into the city with 1500 extra troops, mostly English. He took command on 9 July 1601, four days after the town was invested by the archduke. Vere ensured that the port remained accessible to friendly shipping and was himself transported out by sea that summer, after being shot in the head. He returned in September and continued to conduct a vigorous defence, but against overwhelming odds. By the beginning of December Vere's garrison had lost 40 per cent of its strength and a storm at sea had disrupted a Dutch fleet with reinforcements and supplies. He opened negotiations for a surrender, deliberately aimed at buying time; the fleet sailed in, Vere cancelled his negotiations, and the archduke was left ‘growling and furious’ (Motley, 3.86).

This is one of the more controversial episodes in Vere's career; at the time and later he was criticized, first by those who thought that the negotiations were meant seriously and that the withdrawal of the capitulation offer was only fortuitous; and second by those who felt he had acted dishonourably. His ‘anti-parley’ was defended in a pamphlet, possibly authored by Tourneur (Extremities Urging the Lord General Sir F. Veare to Offer the Late Anti-parle with the Archduke Albertus, 1602). In fact, such negotiations, aimed simply at spinning out time, were common in seventeenth-century warfare; and there is no doubt that the whole thing was a ruse, since the garrison council of war agreed to Vere's suggestion before the anti-parley was initiated. The ploy saved the city and was lauded by the garrison's officers, English, Dutch, and French—no more need be said.

On 7 January 1602 Albert unleashed his greatest assault yet, one designed to storm the entire fortress, rather than merely particular outworks. Vere himself briefly fought hand-to-hand in the breach to repel the main Spanish assault and the garrison held firm. Then, as the enemy retreated, Vere ordered the western sluice of the city to be opened and the retreat was turned into a disaster. A lull inevitably followed as the archduke endeavoured to make good his losses, and in March Vere was withdrawn, as the new campaign season would shortly start and his services were wanted in the field. He made a short trip home where he convinced Elizabeth to raise more troops for service in the Netherlands, then returned as commander of a division of over 7000 Englishmen in Maurice's army. Vere was at the height of his fame and success.

In consequence of his unique place in Anglo-Dutch relations, his diplomatic skill, his prowess in combat, and his popularity Vere had unique authority, greater than that of any other mercenaries in Dutch pay. For example, Vere controlled ‘the apointing of all Captens’ in the English forces (Sydney and others, 2.206). He was also able in these years effectively to thumb his nose at the English hierarchy (save for the queen and Cecil). Lord Grey and the earl of Northumberland fought at Nieuwpoort and Ostend respectively; both objected to having to serve under their social inferior. However, despite frequent complaints at Elizabeth's court, Grey was consistently obliged to defer to Vere; and Northumberland only avoided that fate by a precipitate return to England. In April 1602, during Vere's visit home following his triumph at Ostend, Northumberland challenged him to a duel. He received the dismissive reply that Vere ‘thought it not reasonable to satisfie him after the manner he did require and therefore he would not doe it’ (CUL, Add. MS 9276, fol. 6r)! Northumberland was, in any case, required by the queen to withdraw his challenge. It is unsurprising that Vere also defied the wishes of Essex, consciously choosing to ignore the earl's attempts to advance his clients in the English army; Vere told him to his face that ‘the command of the [English] nation [in the Netherlands] belonged to me’ (Arber, 137), leaving Essex ‘much offended with Sir Francis Vere’ (Letters of John Chamberlain, 1.68).

Increasingly, however, Vere's exercise of power was perceived as arbitrary. In 1603, for example, he was warned about the rumour that he had deliberately blocked the promotion of ‘all Cornish men’ because of a quarrel with a west-country captain, William Lower (BL, Add. MS 32464, p. 62). It was not only the envious Ralegh, Sidney, Grey, and Northumberland who resented Sir Francis; even two of his lieutenant-colonels, Sir Henry Docwra and Sir Callisthenes Brooke, fell out with him. When Vere's behaviour aroused ‘a general discontentment’ (Markham, 307), he took increasingly high-handed methods to maintain order, bullying at least one malcontent captain and winking at a brutal assault on another by his latest lieutenant-colonel, Sir John Ogle. Vere's high-handedness to his own countrymen weakened his position for it made him more dependent on the goodwill of the Dutch, which was becoming less and less unconditional.

Fall

In the early to mid-1590s Maurice of Nassau initiated his celebrated military reforms which eventually helped the Dutch to win their independence. As a result by 1598 the army was both very proficient and under standardized and centralized authority. The autonomy of the republic's English troops, which owed much to Vere's unique position, went against this trend. From 1599 the Dutch expected the English troops, now in their pay, to be as subordinate to central authority as the many other mercenary contingents in their employ.In 1601 attempts by Maurice to remove some English troops from Vere's command led to ‘Hart burning between Sir Francis and his Excellency’ (Sydney and others, 2.228). Between July and October 1602 Vere was almost incommunicado during a prolonged convalescence following a head wound while on campaign with Maurice. During this time George Gilpin, the experienced English ambassador in the Netherlands, died and was not immediately replaced. Vere believed that Maurice used his and Gilpin's absence to increase his authority over the English contingent: an English captain noted that Vere was ‘nothing well pleased with … [Maurice's] dealings by him’ (Salisbury MSS, 12.307).

However, at this stage (1602) the Dutch were still keen to stay on good terms with Vere, taking pains, for example, to ensure his pay was more up to date than that of most of his compatriots: thus in April 1603 he was paid 2600 guilders of his personal salary and perquisites which were in arrears, even though his accounts had not yet been finalized (Nationaal Archief, archief van de staten-generaal, no. 12503, fol. 368r). Evidently his services were still valued and his employers would have hoped that he could be induced to adapt to their wishes. However, Vere was then in dispute with the states general through much of the winter of 1602–3 over the terms of his and his soldiers' employment; and his old teacher Browne, now lieutenant-governor of Flushing, reported that he was on poor terms with Maurice of Nassau. Vere was showing no signs of being willing to make the adjustments that the Dutch required. However, in his favour was the fact that he was still the favoured generalissimo of the head of state of the republic's major ally.

On 24 March 1603 Elizabeth died. Her successor, James of Scotland, had peace with Spain as his prime foreign policy objective. Maurice and the states had a golden opportunity to subjugate fully their English employees and made moves to limit further Vere's authority. They focused attention on Vere's judicial powers which were wholly exceptional: by 1603 all troops in the Dutch army were subject to the jurisdiction of the high court of military justice. Vere and his supporters, believing that ‘the title of general was merely a show if he had to exercise its power without being able to administer justice’ (Nationaal Archief, Oldenbarnevelt archief, no. 2971, fol. 2r), were determined to resist what Vere regarded as an intolerable encroachment on his authority.

As part of his strategy Vere returned home to win the support of the new king. He had already obtained the continuation of his governorship of Brill by letters patent of 16 April 1603. Vere had promptly proclaimed the Scottish king as king of England and he got on well with James I. Encouraged, Vere decided to bring his dispute with the Dutch to a head. At the end of 1603 he threatened to resign unless his authority over the English troops was confirmed on his terms. He evidently believed that, with the king's support secured, he was still irreplaceable. So confident was he that he made his bid while still in England. Courtiers wrote on his behalf to perceived allies within the Netherlands, and early in 1604 the new English ambassador, Sir Ralph Winwood, presented a strongly worded remonstrance to the council of state in support of Vere's requests. The stakes were high: as one English veteran turned diplomat observed, Vere was in effect seeking no less than ‘absolute command of the English troops in Holland’ (CSP dom., 1603–10, 68).

Unfortunately for Vere by the time his proposals came before the republic's council of state, it would have heard of how ‘the Spanish Ambassador [had been] publicqly feasted by the king on St Stephen's day’ (‘Journal of Levinus Munck’, 249). It was obvious that James intended to make peace; his government's influence in Dutch military affairs, albeit still considerable, was inevitably reduced. In addition, the resentment Vere had aroused among the English officers in the Netherlands meant that the Dutch did not have to worry about disorder within their élite corps if they came to a parting of the ways. Consequently Vere's demands were refused. Having declared that if they were not met then his office of colonel-general of the English infantry would be ‘nudum et inutile nomen’ (‘an empty and useless title’; Nationaal Archief, Oldenbarnevelt archief, no. 2971 fol. 1v), Vere was left with no choice but to resign and by April 1604 he had done so. In retrospect this was probably Maurice's intention from the start of his attempts to reduce Vere's judicial powers in 1603.

Vere was still governor of Brill; he could have remained there, but, badly wounded in body in 1600, 1601, and 1602, and now wounded in pride, he returned to England, where he was welcomed at court. On both sides of the North Sea there was a readiness to pretend that Vere's resignation was due to ill health, which saved blushes all round. However, Vere did not retire; rather (in the language of industrial relations), he had suffered constructive dismissal.

Further career and death

In 1605 the Dutch republic was left reeling by a great Spanish offensive which, it was obvious, would be renewed the following year. In December Vere returned to Brill (which had been governed by a deputy); he did so not simply to resume his governorship, but in the belief (shared by other observers) that the dire straits of the Dutch might compel them to restore his commission.Maurice and other Dutch officials dropped hints of sympathy for their former general, but it cost them nothing to express regret at ‘the clause in the treaty [of London] inhibiting the Governors of the cautionary townes to have command in these warres’ (BL, Stowe MS 168, fol. 345v). Clemont Edmondes, who had carried Vere's dispatches from Nieuwpoort, reflected the reality when he wrote in March 1606 of ‘the jelowsie which the house of Nassau hath of Sir Francis Vere of whom Counte Maurice speaketh much good but geveth litle furtherance’ (BL, Stowe MS, fol. 356v). Ogle and Sir Horace Vere supported Sir Francis's return, but bitter opposition from leading English officers, such as Sir Edward Cecil, who was ‘malcontent’ at the prospect of having to resume a ‘servile ranck’ (De L'Isle and Dudley MSS, 3.257), provided a good excuse for Maurice to reject Vere without causing unpleasantness among his friends at the English court or in the Dutch army.

In the end, in 1606, the states general awarded a pension of 3000 guilders (some £300) per annum to Francis Vere; thus bought off, he returned to England, never to lead men in battle again.

In June 1606 Vere was appointed governor of Portsmouth, with subsidiary grants of other offices in that vicinity. It is notable that though England's coastal fortresses were generally run down in the years of peace that followed the treaty of London, ‘enormous sums’ were still spent on the defences of Portsmouth, the garrison and fortifications of which were ‘still in reasonably good condition’ on Vere's death (R. Stewart, The English Ordnance Office, 1585–1625: a Case Study in Bureaucracy, 1996, 119). It is a tribute to the prestige and influence of Sir Francis that he was able to buck the trend of James's pacifist policy in this way.

In later life love found the semi-retired soldier. On 26 October 1607 Vere married Elizabeth, daughter of John Dent, a citizen of London, and his second wife, Alice Grant. Elizabeth was only sixteen; Sir Francis was perhaps three times her age. However, the couple seem to have been happy enough in the short time that remained to them (and it is notable that the same month Horace Vere married a lady sixteen years his junior).

On 28 August 1609, without warning, Vere died. He left no will (a contemporary reported that he left his £300 annuity to the earl of Oxford, but it had been specified in the grant that it should go to Oxford on his death) and a commission for the administration of his property was issued to his widow on 30 August 1609. Their only child had predeceased him. Vere was buried in Westminster Abbey the day after his death, and a magnificent memorial was constructed in the chapel of St John. Modelled on the tomb of Engelbert of Nassau at Breda, it was an appropriate memorial to an Englishman who was among the internationally best known of his time.

The cause of Vere's relatively early death is unknown. However, early in 1605 Ambassador Winwood had observed of Vere's life in semi-retirement that it made ‘his lyfe … unprofitible to the world, and perhaps, as unpleasing to himself’ (BL, Stowe MS 168, fol. 345). Thus, a fellow soldier's speculation that Vere died ‘because he had nothing to do’ may not be far off the truth (J. M. Shuttleworth, ed., The Life of Lord Herbert of Cherbury, 1976, 72). However, Vere had also suffered so many wounds that his body may simply have been prematurely worn out.

The Commentaries

At some point after 1604 Vere recorded his memoirs of several campaigns; these were published in 1657 as his Commentaries. To this surviving text Vere's posthumous editor, William Dillingham, a Cambridge academic, added narratives of Nieuwpoort and the parley at Ostend by Sir John Ogle, written some years earlier; and extracts from some of the publications of Henry Hexham, Vere's page at Ostend and, by the 1630s, a noted writer on military subjects. The resultant work is not only a key source for Vere's life, but one of the major sources for the history of England and the Netherlands in this period.The Commentaries show Vere in a positive light and have been disparaged by some historians as a partisan publication. Other scholars stress that they were not published until forty-eight years after his death and then at the instigation of an antiquary; they assert that Vere wrote a private work intended to aid the military education of future English officers. The great military historian C. H. Firth noted that ‘the object of the Commentaries was not autobiographical’: they were ‘designed to be communicated to a few other soldiers’ (Arber, xvii), and Vere's biographer argued similarly (Markham).

However, there was a flourishing manuscript culture in seventeenth-century England: tracts circulated widely even if unpublished. Ogle had read a copy—but so had Cyril Tourneur, more professional writer than soldier (Arber, 162). The copy of Vere's writings that Dillingham originally saw was in the possession of the distinguished parliamentarian general Philip Skippon, who at the start of his career had served under the Veres, and the other copies he found were in the possession of Sir Francis Vere's great-nephews, grandchildren of Sir Horace: but of these, while Thomas, Lord Fairfax, was also a soldier, the earls of Clare and Westmorland were not. In short, the Commentaries are Vere's version of events for his family, friends, and a circle of admiring veterans, but he would have known the extent to which manuscripts circulated and were copied. Given his grievance over his treatment by Maurice, Vere surely wrote with half an eye on a wider public than simply his own friends and extended family, even if he never intended publication. Moreover, the work may have been left incomplete only by his death; it may be that he intended an autobiography modelled on the Commentaires of the distinguished French soldier Blaise de Monluc, of which Vere would certainly have been aware, rather than military reflections based on the example of Caesar's Commentaries.

In any event there is clearly a self-congratulatory aspect to Vere's writings. Even Ogle, Vere's trusted lieutenant, felt that his own role at Nieuwpoort had been understated by his former commander (Arber, 162). As noted above, John Chamberlain thought that Vere's Nieuwpoort dispatches were self-serving. Vere's original editor commented that Horace Vere's services were ‘so eminent and considerable that they might easily have furnished another Commentary; had not his own exceeding modesty proved a stepmother to his deserved praises’—which suggests that he felt Sir Francis lacked modesty (ibid., 87). Vere's style in his Commentaries attracted opprobrious comment by Samuel Johnson and the great antiquary Thomas Birch, on the grounds that he tried to take the credit for all the actions he described (Markham, 359n.). Into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, historians simply accepted Vere's descriptions of events and lauded him accordingly, but historians writing from a Dutch perspective found Vere's tone distasteful; modern historians of the Netherlands have also questioned the accuracy of how he depicted his relationship with Maurice and his contribution to Dutch strategy (for example, van Deursen, 8; Borman, passim).

In spite of these caveats Vere was an eyewitness of the events he describes for some of which he is a unique source, and he wrote clearly. No one at the time, English or Dutch, questioned his bravery or tactical ability and he was still trusted by Maurice until very late, as even Dutch historians accept (such as van Deursen, 9). Properly used, the Commentaries are an excellent historical source, but given the bias that has been identified in the author, they need to be read carefully, they must always be compared with other accounts of events where possible, and where sources differ Vere's verdict on events should not be accepted simply on his say so. In short, the Commentaries should be treated like any seventeenth-century memoir, and neither privileged nor suspected unduly.

Character

Vere was notable for his calculated rashness. His bravery at Sluys, Nieuwpoort, and Ostend and his frequent wounds all pay tribute to a valour that was remarkable even in an era when courage in combat was common. As we have seen, he was very quick to quarrel when he felt his interests or honour threatened. In this he was no worse than most of his fellow officers and better than some. However, this combativeness may have had a similar cause to Vere's desire, of which we have seen repeated examples, to be given all or most of the credit for actions in which he participated, even when not truly or wholly warranted. His palpable preoccupation with recognition, when his achievements would undoubtedly have brought him great praise in any case, surely hints at a more profound anxiety. Rather than ‘inordinate self-esteem’ (Motley, 4.69), it is possible that Vere had just the opposite problem. For most of his time in the Netherlands he was notorious for ‘his melancholic disposition’ and though a year after he was obliged to retire Browne noted—in surprise—that ‘he love[d] company and mirth’ (De L'Isle and Dudley MSS, 3.257), for much of his life something plainly gnawed deep down in Francis Vere's soul.None the less Vere commanded great devotion. Clemont Edmondes dedicated his best-selling translation of Caesar's Commentaries in 1600 to Vere, and Tourneur published an elegy lamenting his death. Hexham and Ogle remembered their old chief with affection and respect in their writings. Even his rival Edward Cecil, in a tactical treatise written in the 1620s, reminisced that ‘The whole Army both reverenced him and stood in awe of him’ (Dalton, 1.57). Not only former soldiers praised Vere: both the Dutch historian Isaac Dorislaus, holder of the first chair of history at Cambridge, and Thomas May, translator of Lucan and historian of the Long Parliament, viewed his victory at Nieuwpoort as comparable to those of the ancient Romans: there was no higher compliment in Renaissance Europe, where the Nassaus read ancient Roman authors when seeking tactical inspiration. Nor was such praise surprising. Vere was not just a victorious commander: he was also a man of humanistic sympathies. At the sack of Faro in 1596 he saved the library of the distinguished Spanish scholar Osorius and later deposited it in the Oxford University library, which had been refounded by his old colleague Bodley. Vere keenly supported Bodley's attempt to create a resource centre for protestant learning at Oxford: he was one of the first donors in 1598, and followed his £100 present then with regular donations in the following ten years, as well as further gifts of books in 1602, 1607, and 1609, including ‘China books’ (provenance unknown) (Letters of Sir Thomas Bodley, 168).

Achievements and reputation

Vere became famous in Elizabethan England's great war against Spain, and was the mentor for a generation of English soldiers, many of whom went on to command in the civil wars of the 1640s. Today he is probably the best-known English military (as opposed to naval) commander of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, largely thanks to his Commentaries, and to a florid nineteenth-century biography, The Fighting Veres, by the eccentric Victorian admiral-turned-writer Sir Clements Markham. The existence of the Commentaries, a first-person narrative written in robust style, guaranteed the attention of future generations to its author. Vere was greatly praised by early nineteenth-century writers of military history, who took him as a standard example of a sixteenth-century general; one declared that of the English soldiers of Elizabeth's era ‘there was none whose exploits more justly entitle him to the admiration of posterity than Sir Francis de Vere’ (G. R. Gleig, Lives of the most Eminent British Military Commanders, 3 vols., 1831–2, 1.124–5). A strong attack on him in the 1870s by the great American historian of the Dutch revolt John Lothrop Motley only added to Vere's renown, since Motley's pro-Dutch bias ensured that his negative assessments were not simply accepted. In 1888 Motley was in turn vigorously criticized by Markham in The Fighting Veres, the book that established its subject's fame. Nominally a double biography of Francis and his younger brother Horace, whose military career later matched his brother's, it devoted less than a third to Horace. Only in the last quarter of the twentieth century has there been sustained analysis by academic historians of English involvement in the Netherlands in the late Tudor and early Stuart periods. It has not produced any work on Vere (albeit Wernham's narrative histories of the Anglo-Spanish war are informative) other than a PhD thesis (Borman); but this focuses on his career as commander-in-chief of the royal English army in the Dutch republic between 1589 and 1603, is not a biography, and has not been published. So Vere, though relatively well known, has never been the subject of a full biography; most narratives of his life do not take into account recent scholarship on the period; and interested readers with normal library resources will be able to discover little more about him.What verdict, then, can be reached on his career? Dutch historians highlight his ability at light infantry warfare (for example, Schulten and Schulten, 75), and his fighting withdrawal at Nieuwpoort was masterfully done, but he was also a good cavalry general, as he showed at Turnhout. His fighting qualities made him, according to Ogle, admittedly a devoted supporter, ‘the fittest instrument … that [the Dutch] can advise of if they mean to make an active war’ (Salisbury MSS, 16.306). However, Vere also demonstrated mastery of siege warfare, which was what Maurice valued him for throughout the 1590s. In addition he reorganized the English army in the 1590s, showing a talent for administration. Thus Motley's claim that though ‘an efficient colonel, [Vere] was not a general to be relied upon in great affairs either in council or in the field’ (Motley, 4.69) does not do justice to his all-round abilities.

On the other hand it is going too far to claim him as one of England's ‘great captains’. Motley's claim contained a kernel of truth and was presumably based on the verdict of William Louis of Nassau that Vere (whom he knew well) was ‘een goed kolonel’ but needed further schooling before he could play the part of a general (van Deursen, 8n.). In virtually all the great actions in which he won distinction Vere was a subordinate. Maurice often accepted his advice (or so Vere claimed, though modern historians are more sceptical), and was often semi-detached from the main army, but Sir Francis never exercised a truly independent command (in contrast to Sir Horace) and even if Maurice took his advice every time Vere claimed, it was still the prince who had to make the decisions and bear the responsibility. All in all, Vere's talents were those of an excellent corps commander and/or a staff officer, rather than of an army commander. This judgement is of course anachronistic and approximate, but it offers a guide to where Sir Francis Vere should stand in the pantheon of English military greats. If this assessment is not as high as he (or some historians) would have liked, he was still a very able soldier and diplomat.

Vere is best summed up by contemporaries. In the words of a seventeenth-century biographer,

though he were an honourable slip of that ancient tree of nobility [the earls of Oxford] … yet he brought more glory to the name of Vere, than he took of blood from the family. … He was amongst the Queen's swordmen, inferior to none, but superior to many. (Naunton, 295–6)Cecil elsewhere declared: ‘Hee was the verie Dyall of the whole Army by whome wee knew when we should fight or not’ (Dalton). It is an epitaph Sir Francis Vere might have chosen.

D. J. B. Trim