|

|

|

|

It cannot be foreign to our purpose to notice Robin Hood, under this head, of whom much has been said, and but little known to a certainty. His story, however, has been a favourite subject for the Drama. A pastoral comedy of Robin Hood and Little John, was printed in 1594. Robin Hood's pastoral May Games, appeared in 1624.— Robin Hood, an opera, was acted in Bartholamew fair, in 1730. Robin Hood and his Crew of Soldiers, an interlude, near the same time. Robin Hood, a musical entertainment, was performed at Drury-lane Theatre in 1751; and lastly Shirewood Forest, at present a favourite opera with the public.

In Rapin's History of England, our renowned hero is noticed to this purpose:—That about the time of 1199, lived the famous Robin Hood, with his companion Little John, who were said to infest Yorkshire with their robberies. It has been said Robin Hood was of the Huntingdon family and by necessity was driven to the course of life he pursued.

The popular and animating story of Robin Hood, which we acknowledge to know but little of to a certainty, has been the theme of every age, since his time. The songs, in the Garland, which goes by his name, are simply and historically poetized, & have been the favourites of the lower orders of mankind for each succeeding age. Who were the authors of them nobody knows. They were, most probably, written by various hands, as some have much more the spirit of poetry than others. There remote antiquity is not doubted; but they, most likely, have been varied agreeably to the phraseology of the different periods they have been used.

The birth place of our hero is said to be at Loxley, in Staffordshire. (fn. 4) He is made to be of honourable descent, of which the pedigree inserted from Dr. Stukeley's Palśographia Britannić, in the next page, will testify.

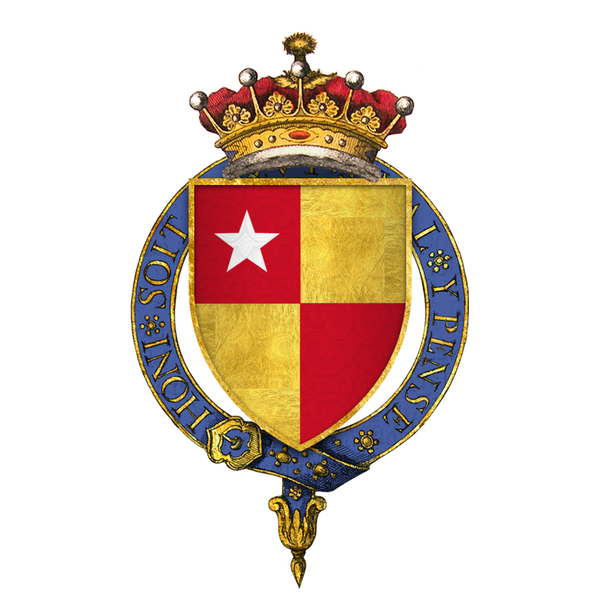

The true name therefore of Robin Hood was Robert Fitz-ooth, but agreeable with the custom of dropping the Norman addition to names, Fitz; and the two last letters th being turned into D, he was vulgarly called Ood or Hood. The reader will discover also, that it is probable he might claim the title of Earl of Huntingdon by reason of John Scot, 10th earl of Huntingdon dying in 1237, without issue, as he was heir by the female line, as descended from Gilbert de Gaunt, earl of Kyme and Lindsey. This title, it seems, lay dormant 90 years, after Robert's death, and about ten of the last days of his life. (fn. 5) His arms were gules two bends engrailed or. (fn. )

From noticing the birth and high connections of Robin Hood, I will notice his life.— Ingeneously it has been observed that this samed robber might be driven to this course of life on account of the attainder of himself or relatives, or on account of the intestines troubles during the reign of Henry the II. when the son of that king was in open rebellion against his father, when devastation, plunder, attainders, and confiscation were the fatal followers of that unnatural contention. The Ferrers being lords of Loxley, the birth place of our hero; and Robert de Ferrers manning the castles of Tutbury and Duffield, in behalf of the prince, William Fitz-ooth, Robert's father, might by his connections with that family or by some such means be implicated in the guilt and consequences of that rebellion. Thus might it happen, that Robin Hood was possessed of no paternal estate, and deprived of the title of Earl of Huntingdon; and this might be also the cause of his taking refuge in woods and forests, to avoid the punishment of his own, or his father's crimes against the state, where he continued, during his life, in a state of actual rebellion; where his little army contended a series of years, successfully, against the power and armies of the king.

Others have conjectured that he was a man of birth and fortune, and had spent his estate in riotous living, which was the original cause of his taking to that mode of life for existence, which his nature seemed to point out to him. Whatever might be the cause of his defection from lawful pursuits, we know not; that the untoward times which succeeded those of Henry the II. might occasion it, is probable.

This celebrated chief of English archers, it is certain, was an outlaw, with many of his followers. Historians have placed his chief residence in Yorkshire; but it is certain, that Shirewood Forest was his favorite haunt. Stow in his annals calls them renowned thieves. Robin had another favorite place near the sea, in the north riding of Yorkshire, (fn. 7) called Robin Hood's Bay. Sir Edward Cook, in his third Institute, p. 197, speaks of Robin Hood, and he observes, that, men of his lawless prosession were called Roberdsmen. The statute at Winchester, 13 of Edward the I. and another the 5th of Edward the III. he observes, were made solely for the punishment of Roberdsmen, and other felons.

Our hero, it is allowed on all hands, had great skill in archery, and much personal courage. His humanity and levelling principles are celebrated by Drayton in his PolyOlbion, song XXVI.

From wealthy abbots' chests, and churches' abundant store, What often times he took he shared amongst the poor: No Lordly bishop came in lasty Robin's way, To him before he went but for his pass must pay; The widow in distress he graciously relieved, And remedied the wrongs of many a virgin grieved.

"Hearne, in his Glossary, inserts a manuscript note out of Wood, containing a passage cited from John Major, the Scottish historian, to this purpose: that Robin Hood was indeed an arch robber, but the gentlest thief that ever was: And says, he might have added, from the Harlein MSS. of John Fordun's Scottish Chronicle, that he was, though a notorious robber, a man of great charity." (fn. 8)

In the vision of Pierce Plowman, written by Robert Longland, a secular Priest and Fellow of Oriel College, and who flourished in the reign of Edward III. is this passage:

I cannot persitly my Pater Noster as the prist it singeth; I can rimes of Robinhod and Randal of Chester.

In Anecdotes of Archery is the following little histoy of this great robber:

Tutbury, and other places in the vicinity of his native town, seems to have been the scene of his juvenile frolics. We afterwards find him at the head of two hundred strong resolute men, and expert archers, ranging the woods and forests of Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and other parts of the north of England. (fn. 9)

Charton, in his history of Whitby Abbey, page 146, recites, "That in the days of Abbot Richard this freebooter, when closely pursued by the civil or military power, found it necessary to leave his usual haunts, and retreating cross the moors that surrounded Whitby, came to the sea coast, where he always had in readiness some small fishing vessels; and in these putting off to sea, he looked upon himself as quite secure, and held the whole power of the English nation at defiance. The chief place of his resort at these times, and where his boats were generally laid up, was about six miles from Whitby, and is still called Robin Hood's Bay." Tradition further informs us, that in one of these peregrinations he, attended by his Lieutenant, JOHN LITTLE, went to dine (fn. 10) with Abbot Richard, who having heard them often famed for their great dexterity in shooting with the long-bow, begged them after dinner to shew him a specimen thereof; when to oblige the Abbot, they went up to the top of the Abbey, whence each of them shot an arrow, which fell not far from Whitby Laths, but on the contrary side of the lane. In memory of this transaction, a pillar was set up by the Abbot in the place where each of the arrows fell, which were standing in 1779; each pillar still retaining the name of the owner of each arrow. Their distance from Whitby Abbey is more than a measured mile, which seems very far for the flight of an arrow; but when we consider the advantage a shooter must have from an elevation, so great as the top of the abbey, situated on a high cliff, the fact will not appear so very extraordinary. These very pillars are mentioned, and the fields called by the aforesaid names in the old deeds for that ground, (fn. 11) now in the possession of Mr. Thomas Watson. It appears by his Epitaph, that Robert Fitz-Ooth lived 59 years after this time (1188); a very long period for a life abounding with so many dangerous enterprizes, and rendered obnoxious both to church and state. Perhaps no part of English history afforded so fair an opportunity for such practices, as the turbulent reigns of Richard the I. King John, and Henry the III.

Hubert, Archbishop of Canterbury and chief Justiciary of England, we are told, issued several proclamations for the suppressing of outlaws; and even set a price on the head of this hero. Several stratagems were used to apprehend him, but in vain. Force he repelled by force; nor was he less artful than his enemies. At length being closely pursued, many of his followers slain, and the rest dispersed, he took refuge in the Priory of Kirklees, about twelve miles from Leeds, in Yorkshire, the Prioress at that time being his near relation. Old age, disappointment, and fatigue, brought on disease; a monk was called in to open a vein, who, either through ignorance or design, performed his part so ill, that the bleeding could not be stopped. Believing he should not recover, and wishing to point out the place where his remains might be deposited, he called for his bow and discharging two arrows, the first fell in the river Calder, the second falling in the park, marked the place of his sepulture. He died on the 24 of December, in the year 1247, (fn. 12) as appears by the following epitaph, which was once legible on his tomb, in Kirklees park; where, though the tomb remains, yet the inscription hath been long obliterated. It is, however, preserved by Dr. Gale, Dean of York, and inserted from his papers by Mr. Thoresby, in his Ducat. Leod. and is as follows:

Hear, Undernead Dis Latil Stean, Laiz Robert Earl of Huntington, Nea Arcir ver Az Hie Sa Gend, An Pipl Kauld Im Robin Heud: Sick Utlaz Az Hi An Iz Men, Vil England Nivr Si Agen. Obit 24 Kal. Dekembris, 1247.

It appears that the inscription was long since obliterated although the stone remains broken and defaced, Mr. Gough has preserved a drawing of it in his Sepulchral Monuments, copied facing page 171. It is said at the end of Robin Hood's Garland, that the inscription was placed on his gravestone by the Prioress of Birksley, (Kirklees.)

What may be gathered, from the celebrated Robin Hood's Garland, respecting his birth, life, and family connections, are briefly as follows; by which the reader will find, who has not condescended to peruse those ancient songs, that this humble relation of him agrees not, in some instances, with the account above, viz.

The father of Robin was a forester, and could send an arrow two north country miles at a shoot. That his mother was niece to the famous Guy earl of Warwick whose brother was a notable 'squire, who lived at Gamewell Hall, in the county of Nottingham. (fn. 13) — That his uncle, whose name was George Gamewell, was desirous of having our young hero to live with him; but his attachment was rivetted to field sports and unbounded freedom: he complyed not with the offer, went to Tutbury to marry a Shepherdess whom he had seen in Shirewood Forest kill a buck dexterously. Her form, dress and features are thus simply poetized:

As that word was spoke, Clorinda came by, The Queen of the Shepherds was she; And her gown was of velvet as green as the grafs, And her buskin did reach to her knee: Her gait it was graceful, her body was straight, And her countenance it was free from pride: A bow in her hand, and a quiver of arrows, Hung dangling by her sweet side. Her eye-brows were black, ay, and so was her hair, And her skin was as smooth as glass, Her visage spoke wisdom and modesty too, Sets with Robin Hood, such a lass?

After fifteen years of age, we find that he was expert at the use of the bow, which he used much in the forest, and, we are told, he killed fifteen foresters, who were all buried, in a row, in one of the church yards in Nottingham. By this time he had about 100 followers. His robberies, frolics, clemency, and charity to the poor, soon became the theme of all people. He robbed a bishop and the sheriff of Nottinghamshire, and sported with their persons and characters. He fought with a tinker, a shepherd, and a friar, and others, who handled him roughly. In the song which relates his great exploits before Queen Catharine, we have a picture of his dress:—

Robin Hood took his mantle from his back, It was of Lincoln green, And sent it by this lovely page, For a present to the Queen. In summer time, when leaves grow green, 'Twas a seemly sight to see, Robin Hood had drest himself, And all his yeomandre. He cloath'd his men in Lincoln green, And himself in scarlet red; Black hats, white feathers, all alike, Now hold Robin Hood is rid. And when he came to London court, He sell down on his knee: Thou art welcome Locksley, (fn. 14) said the Queen, And all thy yeomandre.

In one of these songs we have a description of Little John.

When Robin Hood was about twenty years, He happened to meet Little John, A jolly brisk blade, right fit for the trade, For he was a lusty young man. Tho' he was called Little, his limbs were all large, And his stature was seven feet high; Wherever he came, they quak'd at his name, For soon he would make them to fly.

After this meeting of Little John and Robin Hood, the ballad informs you that they fought, in which combat the latter was worsted; but after the fight, a little persuasion made Little John join this band of merry-making robbers. As the latter part of this ballad is particularly descriptive of the manner this little host of warriors lived; and of the changing of John Little's name to that of Little John, and as the poetry is not the most indifferent in the Garland, I give it here:

There's no one shall wrong thee, friend, be not afraid, These bowmen upon me do wait. There are three score and nine; if thou wilt be mine, Thou shalt have my livery strait And other accoutrements fitting also: Speak up, jolly blade, never fear, I'll teach you also the use of long bow, To shoot at the fat fallow deer. O here is my hand, the stranger reply'd, I'll serve you with all my whole heart; My name is John Little, a man of good mettle, Ne'er doubt me for I'll play my part. His name shall be alter'd, quoth Will Stutely, And I will his godfather be; Prepare then a feast, and none of the least, For we will be merry, quoth he. They presently fetch'd in a brace of fat does, With humming strong liquor likewise; They lov'd what was good; so in the greenwood, This pretty sweet babe they baptiz'd. He was, I must tell you, bat seven feet high, And, may be, an ell in the waist; He was a sweet lad, much feasting they had; Robin Hood the christening grac'd, With all his bowmen, which stood in a ring, They were of the Nottingham breed; Brave Stutely came then, with seven yoemen, And did in his manner proceed; This infant was called John Little, quoth he, Which name shall be changed anon, The words we'll transpose, so where're he goes, His name shall be call'd Little John. They all with a shout made the elements ring; So soon as the office was o'er, To feasting they went, with true merriment, And tippled strong liquors, gillore. Then Robin he took the pretty sweet babe, And cloath'd him from top to his toe In garments of green, most gay to be seen, And gave him a curious long bow. Thou shalt be an archer as well as the best, And range in the greenwood with us, Where we'ill not want gold nor silver, behold, While bishops have aught in their purse We live here like 'squires or lords of renown, Without e'er a foot of free land; We feast on good cheer, with wine, ale, and beer, And every thing at our command. Then music and dancing did finish the day, At length when the fun waxed low, Then all the whole train the grove did refrain, And into their caves they did go. And so ever after, as long as he liv'd, Although he was proper and tall, Yet nevertheless, the truth to express, Still Little John they did him call.

The last ballad speaks of his death after fighting, desperately, with a party of the king's forces, on the 30th of June, under a valiant knight, who was slain in the contest. Bold Robin being taken ill soon after.

He sent for a monk, who let him blood, And took his life away; Now this being done, his archers did run, It was not a time to stay. Some went on board, and cross'd the seas, To Flanders, France, and Spain, And others to Rome, for fear of their doom, But soon returned again.— Thus he, that never fear'd bow nor spear, Was murder'd by letting of blood. And so, loving friend, the story doth end Of valiant bold Robin Hood.

From Robin Hood arose these proverbial expressions, first in the county of Nottingham, and then all over England. (fn. 15)

Many talk of Robin Hood who never shot in his bow.

This certainly alludes to people who talk of things beyond their knowledge.

To sell Robin Hood's penny-worths.—This alludes to things sold come lightly by.

In a small grove, part of the cemetery belonging to Kirklees Priory, is a large flat gravestone, on which is carved the figure of a Cross de Calvary, extending the whole length of the stone, and round the margin is inscribed in Monastic characters:—

Dovce: Ihu: De: Nazareh: Donne: Mercy: Elizabeth: De: Stanton: Priores: de: Cette Maison. (fn. 16)

The lady whose memory is here recorded, is said to have been related to Robin Hood, and under whose protection he took refuge sometime before his death. These being the only monuments, remaining at the place make it probable, at least, that they have been preserved on account of the supposed affinity of the persons over whose remains they were erected.

R. Hood's mother had two sisters, (fn. 17) each older than herself. The first married Roger Lord Mowbray; the other married into the family of Wake. As neither of these could be prioress of Kirklees, Eliz. Stanton might be one of their descendants. (fn. 18)

Of Little John's death, or more properly John Little, which was his true name, who was supposed to be a very tall man, and Robin Hood's prime counsellor, we have the following:—

Antiquarian Rep. Vol. 3, p. 140.

From a loose paper in Mr. Ashmoles hand-writing, Oxford Museum.

"The famous Little John, Robin Hood's companion, lies buried in Hathersage church-yard, in the Peak of Derbyshire, with one stone at his head, another at his feet, each of which, sometime since, had some remains of the letters I. L. and part of his bow hangs up in the chancel, anno 1652."

Near the Abbey, Leicester, stands an upright ponderous forest stone, which goes by the name of Little John's stone; but for what reason none can tell.